- Home

- Stine, Hank

The Prisoner (1979)

The Prisoner (1979) Read online

CONTENTS

One

Two

Three

Four

HANK STINE

THE PRISONER

HANK STINE was a nom de guerre of Jean Marie Stine, author of Double Your Brain Power, Writing Successful Self-Help & How-To Books, and co-author of Best Guide to Meditation. She has also written under the nom de plumes Allan Jorgenson and Sibly Whyte. Her erotic science fiction novel, Season of the Witch (1968) was reprinted in 1995 when the non-erotic movie version, Synapse (Memory Run in Europe), was filmed. In addition to writing Season of the Witch, Jean Marie Stine has served on the Board of Directors of the International Foundation for Gender Education and the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Political Allance of Western Massachusetts. She has written extensively for both science fiction and transgender publications, including Amazing Stories, Transformation, Galaxy, and Transgender Tapestry.

AVAILABLE NOW

THE PRISONER COLLECTION

The Prisoner

by Thomas Disch

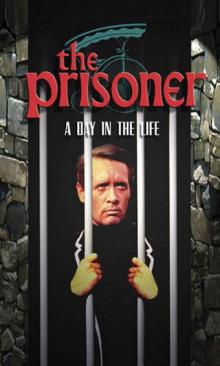

The Prisoner: A Day in the Life

by Hank Stine

The Prisoner: The Official Companion

to the Classic TV Series

by Robert Fairclough

THE PRISONER

A DAY IN THE LIFE

HANK STINE

ibooks

new york

www.ibooks.net

A Publication of ibooks, inc.

The Prisoner™ and © 1967 and 2001

Carlton International Media Limited.

Licensed by Carlton International Media Limited.

Represented by Bliss House, Inc.,

West Springfield, MA 01089-4107

An ibooks, inc. Book

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book

or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

Distributed by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ibooks, inc.

24 West 25th Street

New York, NY 10010

The ibooks World Wide Web Site Address is:

http://www.ibooks.net

ISBN 1-59019-446-2

Cover photograph

copyright © 2002 by Carlton International

For the old reality freaks:

Hedberg, Sandy and Pippin;

And some new ones:

Rudolph, Goldsmith and Karen.

Music pounds out of the car’s speaker with a steady insistent rhythm and the singer’s voice sets up an eerie summons, high and compelling. It is a rock song, White Rabbit. Hard as daylight, the song wails on—the shadows of overhead trees dappling and swirling off the car as it roars down the highway and into the city.

The driver’s face is grim and set. Eyes, chin, plane of the face, tightness of mouth, determined, stubborn and intractable. A dark blue scarf blows back from the throat of his jacket and his eyes stare intently ahead. The woman’s image is conjured in the darkness of his mind, behind the brightness of London, its flat greens and sooty stone.

The car moves smoothly through the traffic, passing, turning and accelerating with a swift, sure expertise. The man’s face is set unswervingly into the pounding uncertainty of the music. His eyes glitter and he smiles grimly, taking out a cigar and bringing it to his lips. Music and city blend into one kaleidoscopic rhythm: concrete and drums.

The music reaches an eerie, wailing climax, and the car drops down a ramp into an underground garage.

He gets out of the car and goes up to giant, double doors, throwing them open with a defiant downward jerk of his arms. He comes to a desk, glares at its occupant, whips an envelope from his pocket, slams it on the blotter, turns, exits.

A card goes up from a computer. Typewriter keys slam against it. The man’s photograph is xxx’ed out.

The card passes down a conveyor, drops in a file. The file shuts. Its legend moves into the light: RESIGNED.

The man’s car roars back through the traffic. His eyes gleam and there is a ruthless tilt to his jaw. A hearse is parked at the kerb before his house.

He gets out and goes in. Two men in black high silk hats, with black kerchiefs at the neck, look up after him.

He throws a group of travel folders in an already packed valise and begins to close it. A white fog swirls up about him. He turns and looks. A jet of gas comes in through the keyhole.

He straightens: the room spins.

The spire of St Paul’s, seen through the window, spirals in against him. As he falls, his arm knocks the valise to the floor. Clothes and folders spill upon the carpet.

One of the folders falls flat beside his face. A name is printed beneath white gingerbread houses with grey-gabled roofs: PENRHYNDEUDRAETH: PORTMEIRION.

One

Some mornings it was:

‘Guten Morgen, Nummer Sechs.’ Number 105 straightened from her rose bushes and fluttered roughened, pudgy fingers at him.

‘Wie geht es Ihnen?’

This interest seemed to please her, and she smiled, tucking a straying grey hair back beneath her scarf. ‘Gut, danke, und Ihnen?’

‘Gut, danke.’

Beyond her yard, the street widened, winding down along the green, past the grocer’s, to the sea.

Ting-a-ling-ling.

The bell above the door rang sharply in the dim, musky interior.

Number 87 looked up from the morning paper. ‘Ah, it’s you, Number Six.’ His fat cheeks bowed in a smile. ‘I’ve been expecting you. That order of pickled herring just came in.’

‘I’d also like a half-dozen eggs, a five pound bag of flour, and some especially sharp cheddar.’

‘Cheddar?’ Number 87 scratched dubiously behind his ear. ‘Oh, yes. Just the thing for you.’ He lifted the flap of the counter and came out around it, going to a group of wooden barrels in the shadow of one wall. He pushed back a cloth cover and produced a bit of rich golden cheese. ‘Try this.’

‘Satisfactory. Quite satisfactory.’

‘I thought you’d like it.’ Number 87 nodded and smiled. ‘How much?’

‘A half-pound, I should think.’

‘Want to make it a whole pound, just to be sure?’

‘No. Definitely a half.’

‘Right-o, Number Six.’ He busied himself weighing cheese, counting eggs, and getting the flour from its shelf. ‘Anything else for you today?’ he said, doing the sum on a length of butcher’s paper.

‘Not today.’

‘That will be one point one five credit units.’

‘Charge it to my account.’

‘Good enough.’

‘And could you deliver this afternoon, about five?’

‘Right-o.’ He rolled it all together in the paper and tied the bundle with a string. ‘I’ll have Number Twenty-four bring it round. That is, if he ever gets here.’ Number 87 frowned, though his eyes remained merry and active. ‘Not dependable, you know. That’s the way with youngsters these days. Not dependable.’ He shook his head in emphasis.

‘Be seeing you.’

Number 87 sketched a salute. ‘Be seeing you, Number Six.’

Ting-a-ling-ling.

There was music playing on the speakers outside, and as the sun brightened, warming, people began to appear on the green and in the windy, gravelled lanes between the houses.

‘Good day, Number Six.’ Number 237 appeared from a side street, sweeping off his battered fisher’s hat and waving. Then he hurried and caught up. ‘Where are you off to today?’

‘A chess game with the Admiral.’

‘Is that right? Never learned myself, you know.’ His scrubbed, honest face furrowed. ‘Not my sort of thing. More a hunting and fishing man, myself. Like to watch wrestling on

TV. That sort of thing.’

He was silent for a moment.

‘You know something, Number Six?’

‘What?’

‘They’re having a chess tournament in Village Hall next month, you really ought to enter.’

‘Why?’

‘It’d be fun. I enter the fishing contest, myself. Won two years running. Not last year though. That was Number Eighty-seven. His first time, too. Going down to sign up now. Want to come with me and enter the chess tournament?’

‘No thank you, Two Thirty-seven.’

‘Well, this is where I turn off. Some other time, maybe.’

His hand swung in a hearty backslap, ‘Be seeing you,’ and he was off along the lane towards the Civic Centre.

Ting-a-ling-ling. The bell above the door rang. Inside it was cool, dark, sweet with the scent of tobacco.

‘Bonjour, Number Six. How are you today?’ The leathery old man continued rolling a cigar.

‘Well enough, thank you, One Fifty-seven. And you?’

‘Pretty well myself.’ He set the cigar aside to dry.

‘You’ll be wanting your specials, right?’

‘Two dozen.’

‘Just a moment.’ He got up and went through a curtain to the back.

Ting-a-ling-ling.

‘Number One Fifty—’ The woman stopped. ‘Oh! Hello, Number Six.’ Her flowered dress swung against too full a figure. ‘I didn’t see you here.’ She looked around. ‘Where’s One Fifty-seven?’

‘In the—’

‘Here I am.’

‘There you are.’

Number 157 placed a box on the counter. ‘Shall I wrap it?’

‘No. I’ll take it.’

‘There’s the strangest thing going on outside.’

‘Here you are.’

‘Thank you.’

‘They’re making some kind of film.’

‘I’ll have to put in a new order soon.’

‘Please do—’

‘Do you know anything about it, Number Six?’

‘—and put this on my account. No, I don’t, Number Thirty-two.’

Her look was speculative and inviting.

‘That’s too bad, Number Six. How about you, One Fifty-seven?’

‘What’s this about a film?’

‘There.’ She pointed through the window. Four young men stood around a camera, and a fifth stood behind it, eye to the lens, face hidden, looking through it towards the shop.

‘Qu’est-ce que c’est que ceci? What are they doing to my store?’

Ting-a-ling-ling.

One of the youths came through the door, stuffing a handkerchief into the hip pocket of his denim slacks. ‘Hiya, pops. My mates and me’—he indicated the others around the camera—’are doing our term project in Film-making. You remember, the course was announced last spring. And we were wondering if you wouldn’t mind if we took some shots of you at work?’

‘Me? Working? Je ne compre—I mean: Why?’

The youth shoved his hands into the pockets of his black leather jacket. ‘Well, it’s a kind of documentary. There’s so much to do and see here, so many interesting people and events, that we…my mates and me…we thought we’d try to show the old and the new. What it has been like and what it will be like.’

‘Oh. Oui. Whatever you like.’

‘And you, sir,’ the youth smiled: blond and engaging. ‘I didn’t catch your number.’

‘Don’t you know?’ Number 32 said. ‘This is Number Six.’

‘Gosh, is that right, sir. I’ve heard a lot about you.’

‘Have you?’

‘Oh, yes. A great deal. They think highly of you in this Village.’

‘Do they?’

‘Yes. Me mother talks about you sometimes. And me mate, Number Twenty-four. He says you’re a regular sort. Would you like to be in our film? I’m sure everyone would like to see you. You’re not out much, I hear.’

‘No, thank you. I’m already late for an appointment.’

‘Say, that’s too bad. Some other time?’

‘Perhaps. Good day—’

‘Number Five Sixty-nine.’

‘And to you, too, Number Thirty-two.’

‘Where are you going?’

‘To chess with the Admiral.’

‘The Admiral. Say, I’ll bet he’d be a good subject for our film. He’s been here longer than anybody.’

‘A bientöt, Number Six.’

‘Be seeing you, One fifty-seven.’

‘Say, Miss—’

‘Thirty-two. But it’s Mrs really. My husband died.’

‘That’s too bad.’

‘Oh, it was some time ago.’

‘Well, would you care to—’

Ting-a-ling-ling.

A sharp, cool breeze had sprung up from the sea, smelling of salt water in the sleepy afternoon sunshine. The group around the camera glanced up curiously, then turned back to their conversation.

Down the beach (past the deck chairs with their red and white striped umbrellas) the Village Restaurant was just opening. Number One Twenty-seven was busying herself about the patio tables, whisking off the night’s residue of grit and moisture, and preparing for the day’s clientele. She stopped for a moment and waved: the fragile face beneath her tarnished blonde hair showing no trace of the bitterness that had led her to attempt suicide in the water so near at hand.

‘Ah, Number Six. Been wondering when you’d get here.’ The Admiral displayed the open board, figures ranked upon it.

‘Good day, Admiral. Sorry to be late.’

‘Think nothing of it. Happened to be late myself. A touch of stiffness in my bones this morning.’

‘Nothing serious, I trust.’

‘Damme, lad, only an old man’s aches and pains. Don’t give it a second thought.’ His huge gentle fingers opened to reveal two pawns: one black, one white. He hid them behind his back, then held out both hands, palms closed. ‘Choose.’

‘That one.’

The right contained: black.

They made the traditional opening: Queen’s pawns to Queen’s four.

The new girl came out, wearing a terrycloth robe over her swim suit, and moved one of the chairs into the sun, using a towel for a pillow. Sunlight gleamed off the silver lenses of her glasses.

‘She’s a looker, eh, lad? What do you think?’

‘Haven’t met her.’

‘Always a cautious one, you are.’ He brought his cane around and leaned his chin on the ferule. ‘Know her number?’

‘No.’

‘Number Seven.’

‘Your move.’

‘Eh, lad. Oh, yes.’

The Admiral’s face composed itself line by fold by jowl into an exaggerated concentration, and he placed a finger beside his nose, peering blearily down at the board. Then he reached out, lifted an ivory figure, and set it down on a white square, vulnerable and tempting.

Reply:

Pawn took pawn.

The old man smiled, moved a Knight in reply.

‘Knight to Queen’s Bishop three. You prefer, then, Admiral, the Scotch opening?’

The play went swiftly.

‘What? Castling so soon?’

Somewhere, out of sight, a brash young band swung into a Beatles tune, Michelle.

Four moustached young men in gaudy silk uniform led the band. Behind them a group of men marched in Salvation Army grey. Their leader had the hangdog look of the existentialist intellectual, steel-rimmed glasses, a French horn, and a chartreuse suit with red piping. He was followed by a shifty-eyed, big nosed trombone player in pink with blue braid; a sweet-faced choirboy fingering an oboe; and last: a stern-faced lad in a scarlet tri-corn.

Down the beach the girl in the bathing suit had turned in her chair and lifted her glasses for a look.

She was beautiful.

And some mornings it was:

‘You there, Number Six, wake up.’

The cool grey light of the tel

evision flickered against the living-room floor and its speaker rattled with sharp, insistent demands.

‘Get up, Number Six. I want to talk to you.’

The bathroom tile was cold, the tap water icy and fresh.

‘You haven’t been adjusting, co-operating. Why is that? Is there anything we can do to make your stay more comfortable? Is there something you lack?’

But the shower was hot. Steam rolling up the walls in a pebbly grey finish.

‘We have tried to satisfy you, tried to help you fit in. Just what is your problem? We’ll be glad to help, if only you’d ask. That’s all we want, really, to make you happy here. What is it? What can we do? Answer me, Number Six. Do you hear? Speak up.’

A small sauce pan, a large pat of butter, a quarter cup of flour, some salt, a pinch of cayenne, and milk.

‘Speak up. I will not tolerate this silence. It is your duty as a citizen to speak. I demand you answer me.’

The yolks of four eggs beaten until thick (the shining metal blades cutting into the rich yellow vitelline).

‘Answer me. Speak up. I’m warning you. I won’t tolerate this kind of disobedience. You can’t flout authority in this manner. You can be made to speak, you know. There are ways of dealing with you.’

Then the whites, whipped to stiff peaks.

‘Come in here where I can see you, this instant. I will brook no further delay. I want to see you and I want to see you now. I know you’re in the kitchen. You’re always in the kitchen. You’ll make some woman a wonderful wife someday. Your culinary expertise is well known. Now get in here and listen.’

Fresh, springy bits of cheddar dropped into the pan, and the flat plastic blade of the spatula stirring it in.

‘There simply isn’t room in this Village for someone who will not co-operate. We all have to work together to make it a fit place to live. And it will take all our efforts. The welfare of this Village must come before that of any one individual. Surely you see that?’

Then the yolk into the cheese batter and the mixture over the whites.

‘We can only progress if we progress together. We must work in harmony and good fellowship. That’s the only way we can build a community free from distrust, dissent, and unhappiness. One family, working together, playing together, living together. That’s our ideal, a true mutuality of mankind. If you would seek to know what you could do for others, not what they might do for you, you would find rewards of which you have never dreamed.’

The Prisoner (1979)

The Prisoner (1979)